In-store dietitians, a growing discipline in the US, offer twin benefits. They both help increasingly confused consumers with their healthy food choices, and help healthier brands by amplifying their messages. They play an increasingly valuable role in a crowded supermarket where good messages can get lost in the cacophany of tens of thousands of products. By Dale Buss.

Kristina Swanson is on the front lines of the struggle between America’s typically unhealthy diets and the better-for-you revolution: She’s the in-house dietitian at Hy-Vee supermarkets in the Upper Midwest.

Swanson interacts daily with shoppers who have all manner of questions about how to eat better; she advises them and guides them to some of the right products. In the process, Swanson serves as an influencer for brands that strive to get the imprimatur of a nutrition expert so close to where consumers actually make their purchases.

“With so many products in the store, it can be really overwhelming for clients and customers to read every label, so having products on a store tour and being able to say that they taste good helps brands,” Swanson told New Nutrition Business. “They’ll send us samples to try, inform us about their products, tell us about dietary tag lines like ‘low sugar’ and ‘gluten-free.’ There have been some great options that we can recommend to customers that really have helped transform habits.”

The idea of a retail dietitian echoes the growth of consulting roles in retail pharmacies, and many supermarket chains have their own pharmacies on premises. On a broader scale, the growth of this discipline also reflects how more American consumers are increasingly relying on in-house experts at all retailers of all types of products, to help them navigate the plethora of options and the intricacies of products ranging from iPhones to automobiles.

Some consumer brands swear by their relationships with retail dietitians. General Mills relied on Swanson to help explain and promote its test of Good Measure, a low-sugar line of nutrition bars and savory crisps (see NNB August 2021) that the company introduced on a test last year in 13 of Hy-Vee’s stores in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, where General Mills also is headquartered.

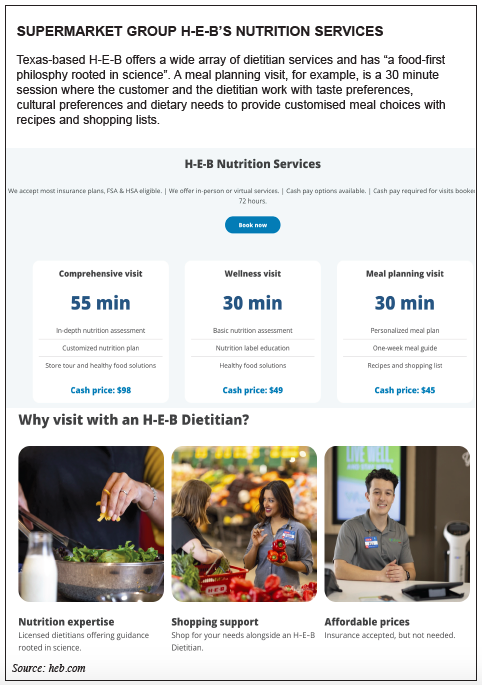

Start-ups also are working with retail dietitians. Afia, for example, a company which markets healthier versions of traditional Syrian street-foods (see NNB March 2022), launched a program with H-E-B, the Texas-based supermarket retailer that has dietitians on staff.

“We give dietitians some information and coupons, and any time they see one of their customers, if they feel like our product fits a dietary need, they walk into the aisle and explain Afia to them and the different ways it can be used,” said Farrah Moussallati Sibai, founder of the start-up maker of frozen falafel and kibbeh, based in Austin, Texas.

While not every US supermarket chain is suited to fielding retail dietitians, or has enough resources to do so, the discipline is growing. A decade ago, there were about 100 of them, a number that grew to about 300 as of five years ago, estimated Phil Lempert, a US-based expert on the industry who effectively markets himself as the “supermarket guru”. Now, he told New Nutrition Business, American retail dietitians number about 1,000.

In fact, Lempert founded an organization called Retail Dietitians Business Alliance that has more than 250 members who network with one another at physical and virtual conferences about their discipline’s growing body of best practices, about particular product lines and attributes, and about how best to deal with a US consumer public that seems to be increasingly interested in dietary advice in general — and, if it’s offered, help in the aisles in particular.

Emily Parent is in the mainstream of the profession and also reflects how it is growing and changing. She and a colleague have staffed the retail dietitian function for several years at Coborn’s, a chain of about 80 supermarkets in the Upper Midwest (see images above).

Amid Covid, Coborn has moved the role of Parent and her colleague to functioning online and via social media. “Now we even go on TV talk shows with six-minute segments,” Parent told New Nutrition Business. Initially, the two women managed the function physically at a handful of stores.

“Most people weren’t familiar at first with the idea of a dietitian in the store,” Parent said. “We provided for the most part free in-store consultations where guests could each schedule a 30- or 60-minute consult with us. We had to educate them on nutrition and also on the idea that a dietitian was available in the store and about what we could do for them. We met a lot with employees, too, so they and our guests recognized that we were the go-to person.

“We would do store tours. We made presentations with pharmacies in the stores, in the community and at health fairs — anything with nutrition. And we were constantly in the aisles.”

Under Parent’s direction, Coborn’s created a program it calls Dietitian’s Choice, a system of company endorsements of about 5,000 products as healthful, supported by a blue logo that appears on shelf pegs by those products. Coborn’s development of its proprietary rating system followed the demise of a high-profile national rating program called NuVal several years ago, after many companies criticized its conclusions.

“We determined guidelines for each food category” for Dietitian’s Choice, Parent explained. “If we’re talking about cereals, for example, we want to have fewer than 10g of sugar, and whole grains, and 3g or more of fiber. Guests can ask questions, but what we’ve found is that they want a black-or-white answer. So while on video and social media, instead of explaining why we endorsed something, we just display the Dietitian’s Choice logo, and people know it’s something we hand-selected.”

- Weight loss is by far the most common concern of customers who consult with her, Parent said. Other popular topics are:

- Paleo diets

- How to go gluten-free

- How to get kids to eat vegetables

Coborn’s dietitians get many referrals from the store’s pharmacies, too. “People are already going there for nutritional questions about diabetes and heart health and for medication,” she said. “So we’ve created partnerships with them.”

About 30%-40% of retail dietitians actually report through the pharmacy. “But there’s a big difference between pharmacy techs and retail dietitians, because the dietitians are really focused on food, and a lot of pharmacy techs are focused on supplements,” Lempert said. “If you have a Vitamin D deficiency, for instance, a pharma will say, ‘Take a supplement,’ but a retail dietitian will say, ‘Eat more mushrooms.’”

More savvy brands have picked up on the usefulness of retail dietitians to their marketing and fund programs for working with them similar to how, for example, they pay allowances to retailers to get more and better space on their shelves. Dietitians “can amplify brands’ messages or sampling,” Lempert said. “But some chains won’t accept any money from brands. If dietitians see a product they like, they’ll just promote it and not ask for anything. Each chain has different objectives.”

Swanson worked with General Mills from the start on Good Measure, providing the company with “some early feedback on the creation of the product,” she said, “then they redid it.” Once the company and Hy-Vee began fielding the new line in stores, she said, “we had signage options, promotions and samples and events such as free blood-sugar and cholesterol screenings.” Customer feedback led to further refinement of the product.

Jonathan Scearcy, who served as head of the Good Measure brand until he recently left General Mills, told New Nutrition Business that Hy-Vee’s dietitian program “helped create awareness and trial. We were a new brand, and we weren’t Cheerios, so people didn’t know about us yet.”

In 2020 before Covid dismantled the status quo in the supermarket business, Sibai said H-E-B dietitians helped explain to shoppers how Afia “could be used in a wrap or with rice or a salad, and then went through all the nutritionals with them. They also knew the story behind Afia, which helped brand awareness.” The cost for such a campaign with that chain is in the tens of thousands of dollars for a three-month period, Sibai said, but she was “hopefully” planning to repeat the effort this year.