As meat analogues and plant milks continue to ride a wave of optimism, we take a closer look at the plant-based category with Paul Hart, an expert in plant proteins. With a career in the world of food science spanning over 40 years, Paul has taken wide-ranging roles in the industry, from ice-cream and dairy to corporate communications, before focusing on plant proteins. Julian Mellentin talked to him about challenges around protein functionality, the nutritional and pricing paradox of Impossible and Beyond Burger, and better alternatives to soy and yellow split pea.

For regular updates from New Nutrition Business, subscribe here.

JM: With all the news about investments in plant-based products, companies could be tempted to see such products as risk-free. Are there any potential challenges?

JM: With all the news about investments in plant-based products, companies could be tempted to see such products as risk-free. Are there any potential challenges?

PH: To deliver a product which has really 100% plant ingredients, the challenge is going to be around functional protein. Take an egg, for example: An egg has functional protein, meaning it’s soluble, it foams, it emulsifies a bit, and you can certainly make a jolly good quiche from an egg – that’s gelation. However, not all plant-based proteins have all these functionalities.

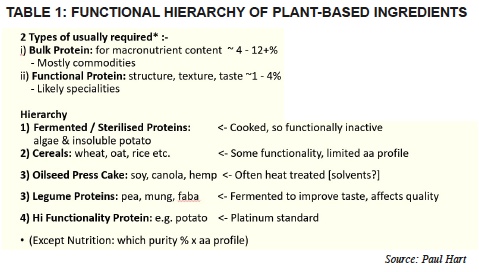

There are two aspects to plant-based proteins: one is to provide the bulk – to dial up the macronutrient protein level – and the other is functional – providing structure and texture – often at a lower value. The problem is that seeds and nuts are insoluble and have low functionality. That’s why plant-based milk often has a layer of something on the bottom that’s not in solution!

What are the plant sources that contain functional proteins that companies could use?

At the bottom of the functional hierarchy (see Table 1) we find fermented proteins from algae or yeast, and insoluble potato protein that many starch companies will produce for animal feed. They don’t do anything because they’ve been sterilised through cooking. Just like cooked egg white: there’s a limit to what you can do with cooked proteins.

Next in this hierarchy are cereal proteins, like wheat gluten or oat, and then oil seed, soy, canola, hemp and sunflower. But then we’ve got the “new soy”, which would be yellow split pea protein. Then other legumes like fava bean, broad bean, mung beans, which have some functionality, although they don’t gel particularly well.

To get the high functionality proteins you need clean green modern separation technologies that don’t involve so much heat.

Why is yellow split pea the “new soy”?

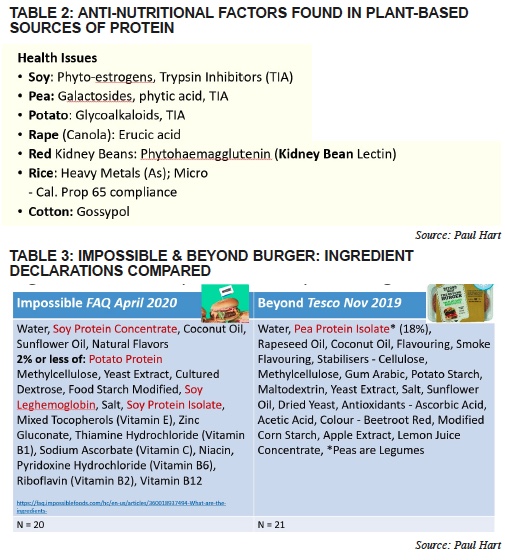

Because it’s not an allergen and it doesn’t have quite the issues around trypsin inhibition activity. Every protein from the plant kingdom comes with an anti-nutritional factor and there are ways to remove it, like heating, soaking and fermenting. In Asia, the ancestral way of dealing with soy is to ferment it. But feeding soy beans directly to humans can bring trypsin inhibition activity, which is a tiny protein that blocks proteases in your gut and thereby limits protein digestion and uptake.

It seems like it’s more difficult to develop a quality food product with 100% plant protein than with an animal source protein.

I think that’s correct… And historically looking back 10 years, that was a particular problem with gluten-free products. Getting a functional plant protein that will work well in a gluten-free system is tricky, and there’s been a lot of dependence on gums and stabilisers.

Some plant proteins, like pea and soy, are widely available, used by many food companies in their products and people eat them. Are there any drawbacks to using yellow split pea or soy beans?

The consumer product that’s most widely available is a plant-based burger that for meat eaters might match the taste and texture of a ground beef burger. Why would vegans want something that looks like a meat burger? My suspicion is they probably don’t. What’s going on here is something to appeal to Flexitarians – people who feel a bit guilty about eating meat and want to go meat-free on a Monday or ‘do’ Veganuary after Christmas.

However, these alternative meat burgers are vastly more expensive than ground beef. And right now there are two big USA companies producing these products: Impossible and Beyond. The Impossible Burger is based on soy and is extending to Asia. It has a GMO yeast-fermented soy leghemoglobin which gives it a blood-red look when people bite into it, which is something they’ve boasted a lot about in their PR in recent years.

However, the Impossible Burger hasn’t entered European markets yet because the European Food Standards Agency needs to consider a safety dossier for the GMO leghemoglobin. Recently we have come to understand that this prevents sales in China too. By and large GMO ingredients are a big red flag to a huge number of consumers in Europe. So it’ll be interesting if they try to market it using the GMO-based ingredient. The Beyond Burger, however, uses pea protein, and that is available in the European market, and also in the UK where it’s available in Tesco supermarkets. Beyond have moved from toll production in the UK to their own production facility in the Netherlands. That is a slightly more benign way of doing things and has a broader acceptance.

The building blocks of protein are the essential amino acids. Is there any difference between the quality of the protein in a pea protein-based burger and the quality of the protein in dairy or eggs or meat?

Yellow split pea and soy tend to have a different amino acid profile and different availability. Soy is a technically complete protein and pea similarly. But pea protein has only about 50% of what the World Health Organisation would recommend in terms of amino acid intake at various life stages. In particular, pea has only about 50% of the required sulphur amino acids – that’s methionine and cysteine.

This problem can be resolved by balancing a legume with something that’s lower in lysine, like a cereal protein. It may come as a surprise, but most ancestral and recent cultures have a cuisine where you have beans and cereals together. For example, beans on toast in the UK, or daal and rice in India etc.

Some traditional ways of eating produce the right balance of amino acids that our bodies need. Do we get the same balance in Impossible and Beyond burgers?

In plant-based burgers, that doesn’t happen. It’s either all soy and not much else, or all pea protein and not much else. Immediately, you will have something that’s going to be out of whack with respect to a steak, or a dairy protein reference like whey.

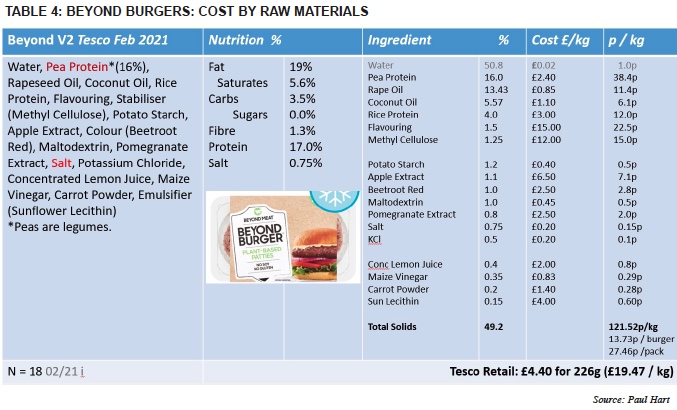

But there’s more: looking at the ingredient profile on some of the plant burgers, we see a slightly odd thing. The Impossible burger has something in the region of 20 ingredients, and Beyond in earlier formulations had over 20. So you’re getting almost two dozen ingredients to make something similar and these additives are not kitchen cupboard ingredients.

Consumers have been telling us for the past 20 years they want ingredient lists as short as possible and as natural as possible. So the ingredient lists of plant burgers like Beyond and Impossible run up against this consumer need.

I term this the “Plant Based Paradox”: all of these ingredients have a supply chain, and require transportation to bring them together. It’s worth reflecting on that for pea protein. Before pea really became a big thing: it was grown in Canada, there was a supply chain from Canada across China. When the mung bean price went up, China started to use yellow split pea starch for glass noodles. When the starch had been got rid of, the pea protein went back to USA, where markets were found for it. That was the early phase from 2010 to 2015. Then it started to gain traction.

You mentioned the relatively high cost of some of the plant-based burgers. What is standing in the way of companies cutting that price?

Compared to simply “ground beef” you’ve got a very long ingredient inventory, and all of these ingredients have their own supply chain, then require warehousing and supply chain management. All of these increase the cost… As a result, in Tesco you’ll find a plant-based burger for roughly £20 ($28/€23) a kilo, while a sirloin steak on special offer can be around £10 ($14/€11) a kilo.

So, animal protein, at the moment, is much cheaper per gramme of protein than one of factory-produced alternative proteins?

We’re told that these types of plant-based burgers are going to get cheaper because they’re going to scale. But, if you create demand for something, more people will enter the market. And what you previously could get becomes unobtainable. The fact that there’s more people seeking demand, doesn’t mean that prices will drop eternally… You will get a reduction through volume purchasing scale but I just can’t see anytime soon the ingredient prices falling to a fraction of what they are now.

A lot of companies are trying to improve the nutritional profile of existing products. How does a plant-based burger stack up against a meat burger nutritionally?

Both Beyond and the Impossible Burger have thought a bit about the micronutrient aspects. The Impossible Burger has zinc, thiamine (vitamin B1), sodium ascorbate (vitamin C), niacin, pyridoxine hydrochloride (vitamin B6), riboflavin (vitamin B2), and of course cyanocobalamin (B12). So they thought about this and they’ve put in a micronutrient pack to maintain some sort of parity.

Long supply chains, the sustainability issue that comes with it, the nutrient profile, long ingredient declaration and cost – these are all problems faced by plant-based alternatives. How could they be resolved?

As for sustainability, companies could use locally-grown legumes to get fibres, isolates and concentrates. If it’s possible to have a supply chain that goes halfway around the world, it’s also possible to rethink it and keep it within country. But that’s going to take five or 10 years to achieve.

As for ingredient declarations, a plant based burger is always going to need more than, say, three ingredients, although it may not need 20.

In terms of macronutrient profile, there’s no fibre or carbohydrate in beef, and in the plant-based alternative, in the absence of a good gelling protein, you need starch, or similar, to give it some texture and adhesion to make your paste formable.

But perhaps there’s another way to get around this issue: you could use yellow split peas whole, rather than fractioning them into starch, fibre and protein. The only problem is that with whole yellow split peas, the ratio of macronutrients is fixed, and you end up with a higher level of carbohydrate.

Is it challenging for plant-based alternatives to claim they are better-for-you if they have an inferior nutritional profile than meat and dairy?

Yes, but I don’t think the message about “plant protein is better for me” is simply because plant proteins are of themselves better nutritionally. It’s appeals to the guilt of meat eaters, concerned about the wrongly stated problem of “meat gives you cancer”.

Plant-based also appeals to people worrying about factory farming, which is – in some countries – ironic. Irish or Scottish beef available in the UK doesn’t come from any kind of factory farm. Then there are overstated fears about greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture… I’m not sure that people believe plant proteins are great because of their nutritional profile. It’s just that meat has received a bad press for so long.

This begs another big question: why is it that the market is all about fake meats, rather than really good plant-based protein? It is possible to bring together really high-quality protein from different plants that add up to an excellent balanced amino acid profile. Well… that’s not an industry where vast amounts of money are made.

And burger substitutes have secured enormous investment. Beyond Meat $500m, Impossible $500m. Private equity and venture capital people seem to be throwing money at meat substitutes made in industrial-scale factories. But they don’t seem to put any money behind burgers made of just nuts and seeds.

I think this is the case. There are other plant-based sources of protein which are superior to ingredients that are most widely used right now. I was visiting a company at the end of 2019 called Aduna, based in London, who trade an interesting plant product called Moringa, sold as a green super leaf powder. It comprises 6% fat, 24% fibre, 26% carbs and 25% protein. That’s quite a good macronutrient profile for a leaf – and the company really cares about their supply chain.

Moringa also contains vitamin A, C, E, K, B1, B6, B12 and minerals potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, and zinc. So it’s coming with a natural nutrient package that you don’t get when you’re buying pea protein or soy protein isolate. The only problem will be chlorophyll which gives you green burgers!